I recently stumbled upon an article in which a Mexican psychologist warned that reggaeton is bad for children’s cognitive growth, fuelling anxiety, confusion and low self-esteem. I found this heartening, not because I delight in the stunted development of the younger generations but because it reinforced all sorts of prejudices I had long harboured about reggaeton, a seemingly ubiquitous musical genre which has been dominating the Spanish-speaking world for what feels like decades, since emerging from Puerto Rico.

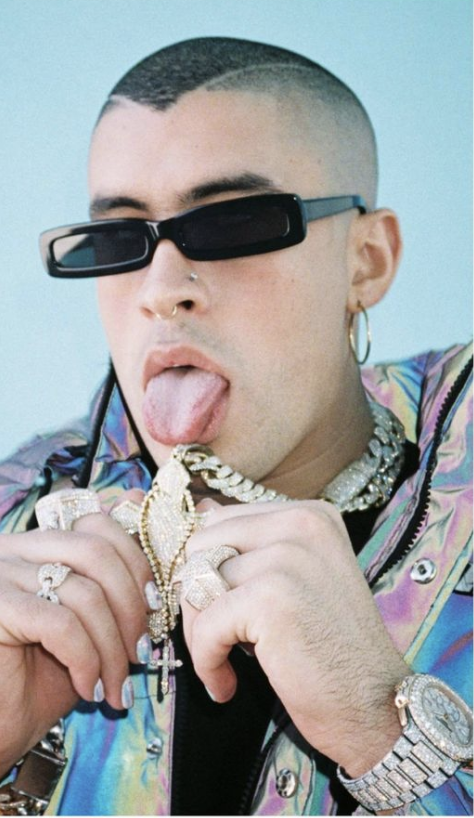

What is it I don’t like? The bog-standard beat which is somehow both soporific and stressful; the sub-fratboy lyrics, which on a bad day can make Gangsta rappers sound like feminists (ie: “You have a big ass/ve-ry big/and I’ve studied it /I’m about to graduate/and on my face I’ll have it tattooed…”); and then there are the childish-yet-creepy artist names: Casper Mágico, Luny Tunes, Bad Bunny.

Full disclosure here: I am one of millions of innocent people who, in the summer of 2017, were scarred by the experience of being forced to listen over and over again to the airwave-colonising reggaeton hit ‘Despacito’ by Daddy Yankee and Luis Fonsi. Those few weeks of my life are now a blur of heat combined with a nagging two-step beat and some lyrics which include: “Oh/ You are the magnet and I’m the metal/I’m getting closer and I’m making a plan/Just thinking about it makes my heart race/Oh yeah…”

But my biggest problem with reggaeton is not the lyrics, the silly names or the repetitive beat. It’s the fact that it just won’t die. In a lifetime we witness endless musical fads, some better than others but virtually all destined to fade. Yet reggaeton has so far had a longer life than New Wave, Acid House, Grunge and Trip Hop all put together. It’s the indestructible amoeba. The morphing variant.

And, if anything, it has gained respectability. In her bestselling memoir of small-town life, Feria, Ana Iris Simón recalls the early days of reggaeton and how it “went from being something crass and vulgar, what they played at the village fiestas where those who wanted to be cool refused to go precisely because there was reggaeton on all the time…to being the main attraction of the Primavera and Sónar [music festivals].” Not only is it ubiquitous, she’s saying, but it also has credibility.

I was recently complaining about all this to a friend. He corrected me.

“You’re looking at this all wrong,” he said. “Reggaeton isn’t a fad. It’s here to stay – like rock ‘n’ roll or hip hop.”

This realisation initially left me stunned. For days I was dismayed by the thought that we are saddled with this rhythmic banality forever. But then came acceptance and the hope that perhaps a new, innovative artist will arrive (Good Bunny, perhaps? Or Mummy Yankee?) to drag reggaeton out of its ghetto of blingy mediocrity and down some adventurous new avenues. But the beat, it seems, will just go on and on.

0 Comments