“Mr Sánchez, you only care about power and we only care about Spain.” – Pablo Casado.

Another crisis hits Spain and once again the country’s political class responds not with unity, statesmanship and deliberation but with tribalism, conspiracy theories and the airing of old grudges.

When Pablo Casado, leader of the main opposition Partido Popular (PP), promised, soon after coronavirus hit the country, to stand together with the leftist government of Pedro Sánchez it was refreshing news. The country’s politics has been so bitterly divided in recent years that it was easy to wonder if only a mammoth national challenge like this could bridge the chasm.

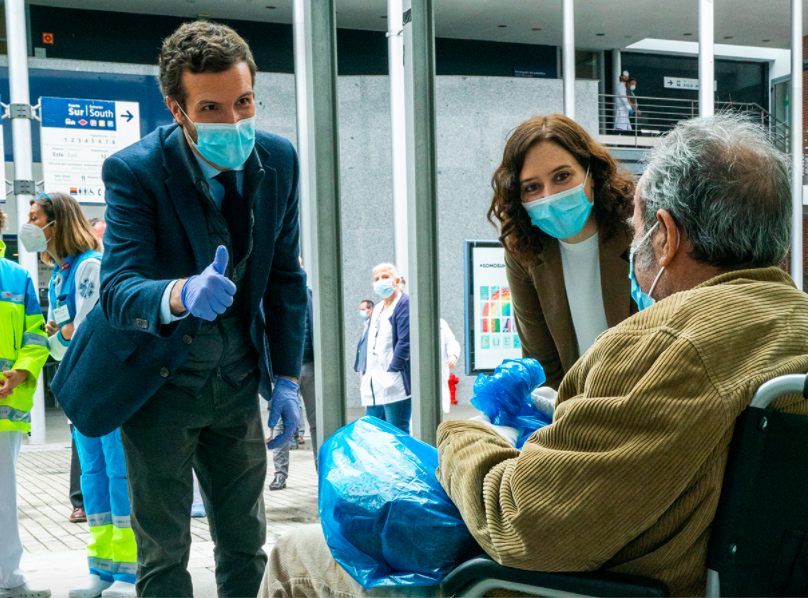

Pablo Casado: Angry, but not really helping. Photo: Partido Popular.

But the truce has not lasted. To be honest, it never really began. According to the PP and Vox, the second- and third-largest forces in parliament, there are two main reasons why Spain has been so hard hit by Covid-19: Pedro Sánchez and Pablo Iglesias. They would like us to believe the spread of the virus and, in particular, the deaths it has caused are primarily the fault of the prime minister and his coalition partner.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing, affording us a view of where the government may have gone wrong. Allowing the massive March 8 Women’s Day marches to go ahead now looks like a mistake, especially as the government itself suddenly changed tack and closed schools just days later, albeit several days before introducing the full lockdown. Like pretty much every European country, Spain was woefully unprepared in terms of equipment and strategy. Sánchez’s communications strategy, meanwhile, has been an unfortunate blend of heavy spin and high-handedness.

A cool-headed look at where things have gone wrong will be needed. However, a rather more pressing issue is how to overcome the crisis. And that is where the political opposition has lost its way, reverting to type as it desperately seeks to apportion blame while refusing to cooperate in the national response.

Casado, for example, has demanded an apology from Sánchez for allowing the March 8 events to go ahead. He has reprimanded him for not wearing a black tie in Congress or hanging flags at half-mast. He has also reminded Sánchez of how, in 2012, his own house was surrounded by angry leftist demonstrators – using this as proof of the Socialist Party’s radicalism. Casado has dismissed Sánchez’s invitation to form a national cross-party pact as “a decoy” aimed at facilitating a change of regime, apparently transforming Spain into Nicolás Maduro’s Venezuela.

You may be forgiven for wondering how any of these proposals or outbursts helps Spain overcome coronavirus. Any country at a time like this deserves – and needs – an opposition that can provide constructive criticism and institutional unity (or “loyalty” to use the Spanish phrase). Few would expect the far-right disruptor Vox to offer such things, and indeed it has not. But it still comes as a shock to see the PP, a party which has itself governed Spain for a total of 15 years, behave like this.

Casado’s party is, after all, well acquainted with the difficulties of national crises. When in government in 2002, it mishandled the listing Prestige oil tanker off the Atlantic coast, contributing to an environmental disaster. The following year, it supervised the misidentification of bodies following the death of 62 Spanish peacekeepers in an air crash in Turkey, compounding the grief of relatives.

It’s also the same party which, in 2004, under then-prime minister José María Aznar, told the nation that Basque group Eta had carried out the terrorist attack that killed 191 people in Madrid. It hadn’t, but the belief that it had was fuelled and perpetuated, like a religious cult, by the party and its ideological allies in the media. The outlandish theory was used to cast the Socialist government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero as illegitimate, a variation on the Trumpian “birther” strategy before such a thing even existed.

Sounds familiar? Sixteen years on, Spain has another Socialist prime minister whose legitimacy the right is casting in doubt. This time it is because he has needed the parliamentary support of a Catalan pro-independence party to govern and that his coalition partner is Podemos, a leftist force which in the past has had links to Bolivarian administrations in South America.

Podemos’s leader, Iglesias, has further fuelled such hostility with his recent celebration of the anniversary of the Second Republic on social media. It was naïve, perhaps, but hardly the proof many were seeking that he is plotting to overthrow Spain’s parliamentary democracy and install an Andean autocracy.

It seems to be his parliamentary dependence on Catalan nationalists and Podemos which are the reason why Sánchez is drawing so much criticism from the right, more than his handling of the coronavirus crisis itself. The problem is, this betrays a deeply worrying conception of democracy, one that was neatly displayed recently by the singer and TV personality Bertín Osborne, who posted on Twitter a video of himself quaffing wine, praising healthcare workers and Spain in general, while complaining about the country’s leaders being there only “circumstantially”.

What Osborne doesn’t understand is that whatever you think of those who have been elected to lead you, they have been elected to lead you. Eventually you’ll get the chance to vote them out of office. Yet this fact has been impossible to digest for those who share the entitled approach of Aznar and his political offspring, who have insisted on dragging their bitter baggage into the coronavirus emergency.

This political nastiness is one of many sub-plots to the current crisis and it belongs alongside the sinister weirdos who daub doctors’ cars with insults and send letters to supermarket workers telling them to move out of their apartment block due to contagion concerns.

Fortunately, there has been a much more gratifying side to the emergency in Spain, that of the tireless healthcare workers, the eight o’clock applause, the online humour and solidarity. And the political right has not behaved as one in recent weeks. Inés Arrimadas, the new leader of Ciudadanos, has appeared to drag her party away from the masochistic tribalism it had pursued under Albert Rivera, towards something more sensible, combining “loyalty” with criticism.

But what coronavirus has done is to place under scrutiny the tired old word “patriotism”. Unfortunately, it has become so twisted and curdled in Spain that it is in danger of meaning little more than wearing a red-and-yellow bracelet and barking “España es un país grande” over and over. As it faces the enormous challenges of the months to come, the country could do without that particular brand of national pride.

A recent poll published by El País reflected how politics is swaying people’s view of this crisis. Forty-seven percent of those asked approved of the government’s handling of the situation; 48 percent disapproved. Last year’s two general elections gave very similar numbers in terms of the split between the parties on the left and those on the right. A right-wing voter is probably not going to approve of Sánchez’s handling of this crisis, whatever the prime minister does. A left-wing voter probably will. Far from eliminating tribal splits and uniting the country, coronavirus has become yet another political battleground in Spain.

History may eventually judge Sánchez and his government harshly for how they have handled this healthcare crisis. But right now it might be just as relevant to ask: How patriotic are you being, Pablo Casado?

0 Comments