“…I believe ardently that real memory, not historical and documentary memory but living memory, will be perpetuated only through literature. Because literature alone is capable of reinventing and regenerating truth.” – Jorge Semprún.

In the early 1940s, as Spain settled into a period of grim dictatorship, one of its exiled citizens was embarking on a series of adventures that would make his life one of the most colourful of the 20th century.

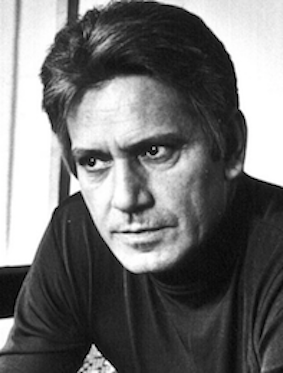

Semprún: Intellect and action.

Jorge Semprún’s biography would beggar belief if it were a piece of fiction. But the facts of it are there in black and white in Soledad Fox Maura’s excellent biography, ‘Ida y vuelta: La vida de Jorge Semprun’, first published in 2016.

The grandson of former prime minister Antonio Maura, young Jorge went into European exile with his Republican-supporting family as the civil war started. Shedding his Spanish skin, the teenager absorbed France’s culture and language before joining the wartime resistance. Arrest by the Gestapo led to a spell in Buchenwald concentration camp. On his release, Semprún fell in with the Spanish Communist Party, which operated out of Paris. For a decade he was an undercover agent in Franco’s Spain, recruiting militants to the cause and reporting on the state of the country. After splitting with the party in acrimony he took on a new guise, that of public intellectual, and he authored (in French) a string of critically acclaimed books, several of them, such as his début Le Grand Voyage, based on his Buchenwald experiences. He also received an Oscar nomination for one of his screenplays and became a prominent member of the Parisian intelligentsia, forging friendships with the likes of Yves Montand and Costa-Gavras. Semprún’s final incarnation saw him make a long-awaited homecoming to Madrid, where he was minister of culture in Felipe González’s Socialist government in the late eighties and early nineties.

Several figures, including Santiago Carrillo, King Juan Carlos and Adolfo Suárez, are frequently touted as representing the vision and spirit of compromise of Spain’s transition to democracy. But Semprún arguably made a more radical journey than any of them: from Communist subterfuge to the institutional pomp of a government ministry. But many also see him as representing something much bigger: the turmoil of 20th century Europe.

Something else which makes Semprún stand out was his cosmopolitanism. Few people travelled abroad in mid-century Spain, yet his embrace of all things French made him bi-cultural (and, thanks to a sadistic, German-speaking nanny, tri-lingual). In addition, with his bouffant hair, good looks and roll-neck sweaters, he had a grace and glamour that were rare for Spanish men of the time. (Fox tells of how he was told to change his cologne while operating undercover in Spain, because his exotic odour risked blowing his cover).

Europe has had few figures who can be placed alongside Che Guevara, yet Semprún’s life and qualities make it tempting to make the comparison: the privileged upbringing, travels to a foreign land where political awakening was accompanied by armed struggle; further travels in which the protagonist, in disguise, attempted to spread the Communist ideology; and in each case, a reputation was earned for both intellect and action. The comparisons end in mid-life – while Guevara died young, Semprún lived until the age of 87.

Fox Maura, who is a professor of Spanish and comparative literature at Williams College, Massachusetts, offers a fascinating insight into each phase of Semprún’s life. She also questions, in a legitimately insistent fashion, whether his venerated status is always justified. One of the patterns of his biography was a repeated falling out with or alienation from people close to him, including his father, brothers, son and Communist comrades. To Semprún’s annoyance, his brother, Carlos, offered what Fox Maura describes as a “Greek chorus” by publicly undermining and downplaying his heroic deeds. The biography is particularly scrupulous in exploring his life in Buchenwald which, the author finds, was more comfortable than that of many fellow inmates, partly due to his grasp of the German language, but also because of his family connections and rapport with Communist prisoners who played a major role in the camp.

Fox Maura carefully examines both the life and literary output of her subject, to find out where fact ends and fictions begins. For Semprún, the most honest way of writing about the horrors of the Holocaust was not through straight reportage, but rather something more embroidered. This leads him to inhabit the very Spanish genre of the pícaro (or picaresque), Fox Maura concludes.

“Through an ingenious process of self-creation, and thanks to the narrative he weaves out of his suffering and personal woes, the pícaro comes to acquire the social status that has always eluded him,” she writes. “The pícaro is a self-made man par excellence, self-made not through work in the capitalist sense but rather through literary ingenuity.” [My translation.]

This is an account not just of one of the most remarkable Spanish lives of recent times, but of one of the most colourful and intriguing European lives of the last century.

‘Ida y vuelta: la vida de Jorge Semprún’ by Soleded Fox Maura is published by Debate and published in English by Arcade as ‘Exile, Writer, Soldier, Spy: Jorge Semprún.’

0 Comments