“Because we are right! And because we are strong!” – Lluís Companys

“Let’s not go to sleep dreaming of Scotland only to wake up in Ulster.” – Lluís Rabell

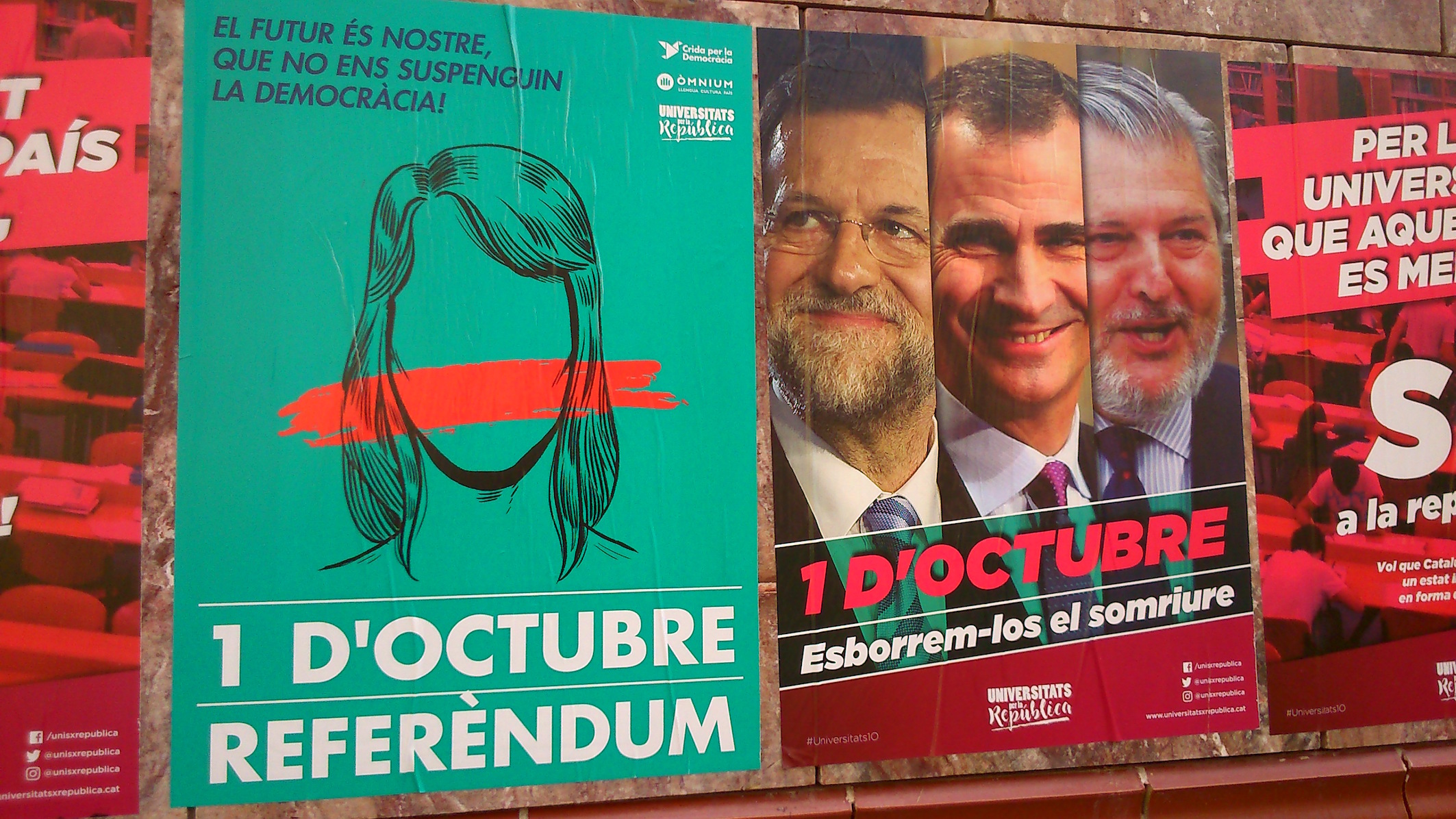

In early October I met up with a Catalan friend in a café in Barcelona. It had been a while since I had seen him and although the last time we had spoken he’d been a supporter of independence, he had also expressed a certain scepticism about the whole process and was able to laugh at its more absurd manifestations. This time, however, his opinion had hardened and his mood darkened. The October 1st independence referendum, which had taken place just a few days earlier, was still fresh in his mind. Friends and members of his family had been in polling stations that had been set upon by the civil guard and national police as they attempted to stop Catalans from voting that day.

My friend recounted what had happened in disbelief, becoming increasingly distraught as he did so. Eventually, he blurted out: “They won’t even let us fucking vote!” and there, in the middle of the café, he started sobbing.

A few minutes later he left and as I was finishing my coffee, a woman at the next table came over and asked if I was journalist. Yes, I said, cagily.

“I couldn’t help overhearing your conversation,” she said, barely able to contain her outrage. “That man was telling some terrible lies.”

To my relief, that was as far as the conversation went. But both episodes spoke volumes to me about this dispute and how it has taken a disturbingly visceral hold of those on both sides.

One of the striking, and at times laughable, fallouts of the Catalan crisis has been how it has reduced apparently rational, adult intellectuals to the level of teenage trolls. It has become fertile ground for a particularly alarming brand of echo-chambered ranting and name-calling, not just between everyday twitter users, but also at the supposedly highest level.

This has presented us with some sights I never imagined I’d witness – such as Julian Assange tweeting in Catalan and then embarking on a very public sandpit exchange with novelist Arturo Pérez-Reverte. That spat told us little more than how easily a couple of grown men could tumble into a pit of infantile gobbledygook. But other, apparently similar, fracas generated by the Catalan situation have been more interesting and perhaps more informative.

In the wake of October 1st, the The New Yorker’s Jon Lee Anderson wrote an account of what had happened that day, putting the police violence at the heart of his relatively short article.

“Whatever the avowed legality of the action, it was not only a shocking display of official violence employed against mostly peaceful and unarmed civilians but an extraordinary expression of cognitive dissonance,” wrote Anderson. “Since when did European governments prevent their citizens from voting?”

That article, and others in the international media, have drawn an irate response from within Spain, at least from the unionist side. The novelist Antonio Muñoz Molina was particularly irked, furiously taking issue with Anderson’s description of the civil guard as a “paramilitary” force. The use of that word alone, Muñoz Molina suggested in El País, showed that this journalist “is deliberately lying, with no qualms he is aware that he is lying and aware of the effect his lies will have…”

Earlier, in a paragraph that should be pored over for years by those seeking to understand the complex, barbed, psychology of modern Spain, Muñoz Molina had written:

They want us to be bullfighters, heroic guerrillas, inquisitors, and victims. They love us so much that they hate it when we question the wilful blindness upon which they build their love. They love the idea of a rebellious, fascism-fighting Spain so much that they are not ready to accept that fascism ended many years ago. They love what they see as our quaint backwardness so much that they feel insulted if we explain to them how much we have changed in the last 40 years…

Several similar articles followed that of Muñoz Molina, many of them published by El País, which seems to have become the standard-bearer for Spanish democracy’s wounded pride. The newspaper’s op-ed department head, José Ignacio Torreblanca, even invented a new word – Anglocondescension – to describe “the insufferable sentiment of Anglo American superiority that we have been suffering since the October 1st referendum in Catalonia.”

Like many of his colleagues, he cited bullfights, flamenco and paella as tropes that lazy foreign journalists apparently lean on when writing about – and talking down to – Spain. In another article – yes, another one – in El País, Maite Rico took issue with foreign observers’ obsession with “bullfighters-civil war-García Lorca-paella” (where does this thing about paella come from?).

I won’t go into how accurate or not the foreign media has been about Catalonia over the last few weeks – after all, the sheer volume of coverage has been overwhelming. But the crisis has opened Spain up to a level of international scrutiny that it has probably never experienced before, given the impact of social media and 24-hour news.

As for the response of Spanish commentators to what the foreign press has been saying about their country over the last few weeks, they seem very much in line with what I call The-New-York-Times-Thinks-We’re-Shit Syndrome (TNYTTWSS) – a serious but little understood pathology that is particularly prevalent in the Iberian Peninsula. Previously, TNYTTWSS manifested itself as a kind of enthusiastic curiosity about what foreign media thought about Spain. But in recent weeks it has curdled into a spiky defensiveness.

Much of the anger of Messrs Muñoz Molina and Torreblanca and others seems to be focused on the constant referencing of the Franco era in coverage (Muñoz Molina’s article was headlined “In Francoland”). Can’t you just forget about our past, they are saying, it has nothing to do with our present. It’s a fair point and their frustration is palpable. But ignoring Spain’s recent past when trying to understand its current political/constitutional/territorial/democratic (take your pick) crisis makes little sense. The country has made huge strides forward in the last four decades, but even its blithest champion would have to agree, for example, that its judiciary has a credibility problem, or that the governing Popular Party’s torrent of corruption scandals go beyond the realms of embarrassment, and that Spanish voters have a disturbing habit of ignoring such aberrations when casting their vote. Do we just write off these phenomena as anomalies, existing without historical background? No, we look for reasons, many – but not all – of which can be found in the hectic years of the democratic transition, or beyond, in the democratic vacuum of the dictatorship.

Similarly, recent oddities such as Brexit or the election of Donald Trump can only be fully understood with the benefit of historical context (whether that be Britain’s colonial past and waning international influence, the decline of the US rust belt and longstanding racial tensions, and so on). But looking hard at a country’s democratic credentials and recent history when it sends armed riot police in to deal with unarmed voters, or jails pro-independence leaders indefinitely as part of a probe into rebellion and sedition is not unreasonable or part of an international plot to diss Spain. It’s common sense.

Anderson’s article, it has to be said, did lack some more recent context. He didn’t mention the undemocratic behaviour of the Catalan pro-independence parties in late 2015, when, after failing to win 50 percent of votes in a plebiscite-election, they declared victory and handed themselves a mandate to push ahead towards secession. Nor did he mention the highly dubious behaviour of the Catalan parliament on September 6th and 7th of this year, when the speaker altered the order of the day in order to allow two contested laws paving the way for independence to be steam-rollered through the house.

But, for some time now, both sides in this dispute have been gleefully “spitting upwards”, as the Argentines would say.

For Carles Puigdemont and his Catalan government that meant using a series of legitimate grievances against the Spanish state and government to push on towards a hazily sketched-out independent republic, regardless of legality and the wishes of a majority of Catalans, even when it became clear that declaring independence would accelerate the flight of companies from the region and rob it temporarily of its existing devolved powers.

For Mariano Rajoy it has meant pandering to the basest instincts of the right wing of his party, the Madrid media and his voters, by refusing even to acknowledge that this was a political problem. For 24 hours – on October 1st – Rajoy was the prime minister of a country that resembled a banana republic. Since then he has found himself forced to resort to the most drastic response available: direct rule. This most unionist of politicians has done more long-term damage to the nation’s territorial unity than any Spanish leader in recent times. If Catalans still commemorate the fall of Barcelona to Bourbon troops three centuries ago, you can bet October 1st 2017 will stay fresh in their memory for some time to come.

The spit, as the Argentines might say, has only just started landing.

0 Comments